Corporate bonds are a well-established part of the investment universe for insurers and pension funds but is this asset class starting to give rise to concerns about the risks it might pose?

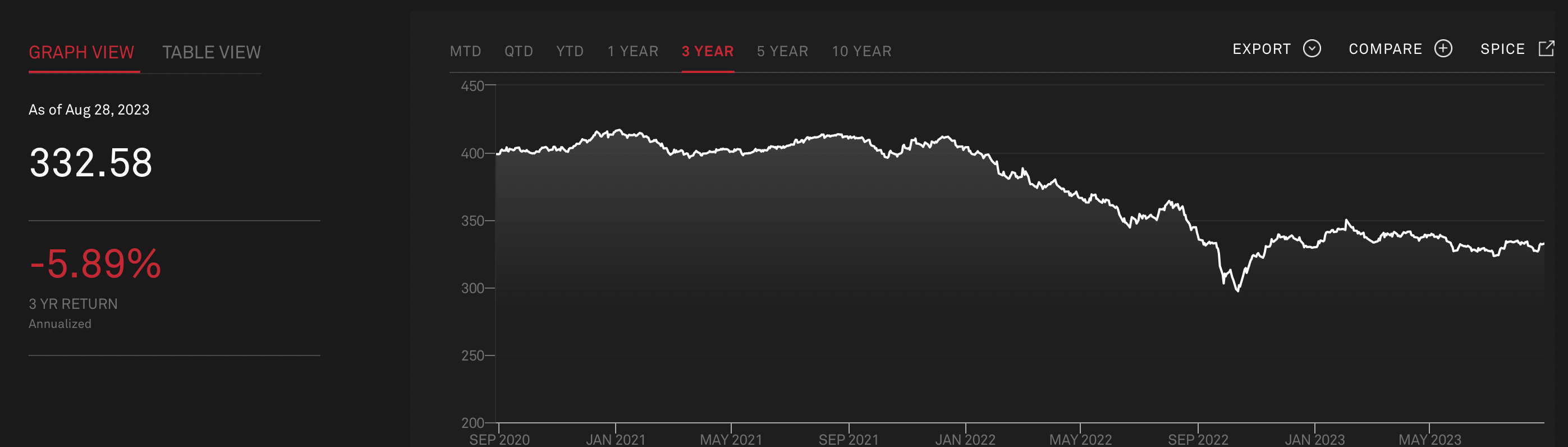

Corporate bonds have e xperienced something of a bumpy ride in the last few years, with the S&P UK Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index showing no recovery since the battering the corporate sector took during the pandemic (see chart left).

xperienced something of a bumpy ride in the last few years, with the S&P UK Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index showing no recovery since the battering the corporate sector took during the pandemic (see chart left).

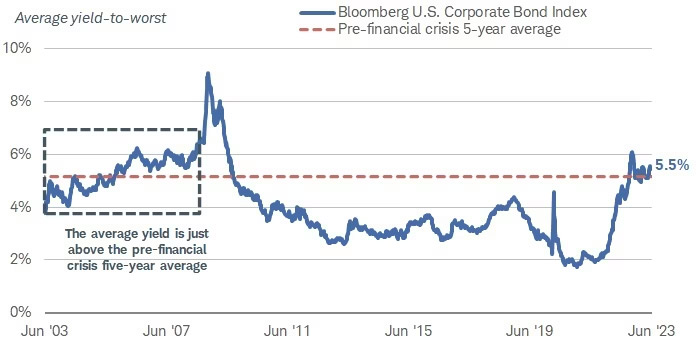

US bonds have fared better. According to the Bloomberg index the average yield on US corporates has just clawed its way back to the relatively healthy average levels of 5.5% it enjoyed before the global financial crisis (see chart right), writes contributing editor David Worsfold.

This might all seem part of the normal ebb and flow of investment returns for an asset class readily influenced by broader macro-economic factors, but at the end of last week, a blog appeared on the Bank of England website gently raising some concerns about the stability of the market and its potential to create financial instability.

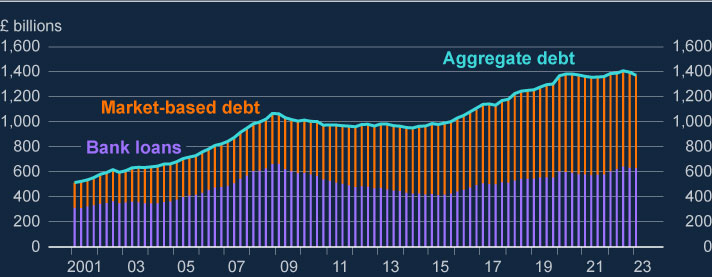

It focussed on the significant increase in the proportion of corporate debt provided by market-based finance (MBF) (see chart A below). Since the global financial crisis, nearly all the £425bn net increase in UK corporate debt has come from MBF.

This has benefits but also creates risks, said the blog’s authors:

“MBF can, in theory, help provide diversification of funding sources and increase the resilience of the supply of finance to corporates. But it can also introduce additional vulnerabilities (eg the crystallisation of risks in MBF could amplify economic shocks and disrupt the provision of financial services to UK corporates). This makes it vital for the Financial Policy Committee to continue to identify vulnerabilities and seek to mitigate those risks.

“UK corporates have been experiencing headwinds from higher interest rates and the subdued macroeconomic backdrop. Consequently, riskier borrowers seeking MBF had experienced a more subdued appetite from investors, with the primary market for high-yield bonds closed in parts of 2022. Over 2022, where parts of the market were shut, around 8% of high-yield bonds fell due, although these issuers had recourse to other sources of credit such as revolving credit facilities or deleveraging. Furthermore, there were no new leveraged loan issuances in 2022 from firms with more than six times debt to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation.”

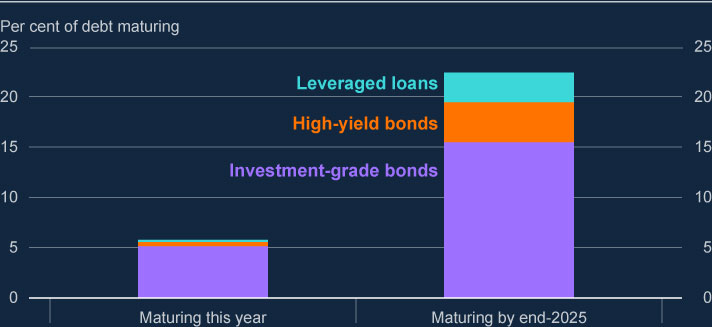

It is refinancing this growing debt pile that is causing brows to furrow in Threadneedle Street. They do not see it as an immediate problem but are marking the card of bond holders and issuers about the potential for a refinancing crunch in 2025, arguing that the maturity profile of debt impacts the rate at which corporates are exposed to higher interest rates. With the projections for interest rates leaning markedly towards a higher for longer scenario it is these medium term refinancing pressures that could pose a risk to financial stability.

“The near-term refinancing risk appears relatively limited”, say the authors.

“Corporates tend to refinance their debt around 12–18 months before it comes due. So, we look at both the amount of debt due for refinancing this year (6% for corporate bonds and leveraged loans combined) and cumulatively by the end of 2025 (22%) (Chart B below right). Both are well within year-on-year typical ranges.

“However, it is not typical for riskier corporates to be able to switch lending markets. For example, non-investment grade issuers cannot easily access the investment-grade bond markets. This exposes corporates in riskier credit markets such as leveraged loans, private credit and high-yield bonds to greater risks. Around 2% of leveraged lending is coming up for refinancing this year, this compares to 30% by end 2025.”